Kat Rosenfield at the Free Press has a fascinating essay about the recently announced bankruptcy of DNA testing company 23andMe, in which she reminds readers of “the solipsistic, race-crazed fever dream that was American culture in 2017.” That was the year 23andMe got a surge of popularity due to an endorsement from Opray Winfrey. It was also the year that Donald Trump began his first term as president, and roughly half of America — the half that voted for Hillary Clinton — went completely psycho.

Any study of Trump Derangement Syndrome would have to begin in 2007, when it seemed that Hillary Clinton would inevitably be the next Democratic presidential candidate. Then she stumbled in Iowa, where the upstart Barack Obama won the caucuses, and suddenly the progressive grassroots of the Democratic Party fell head over heels in love with a narrative: THE FIRST BLACK PRESIDENT! There was also the fact that the grassroots had never forgiven Hillary for her vote in favor of the war in Iraq, but the rhrilling prospect of electing THE FIRST BLACK PRESIDENT was the real juice that drove the Obama steamroller which flattened the Clinton machine in the Democratic primary campaign. So after Obama had been elected and reelected, then at last it was her turn, and the Establishment wing of the Democratic Party made sure that Hillary was the nominee, despite the Bernie Sanders challenge.

The essential argument of Hillary’s 2016 campaign — the big selling point — was that she represented The Right Side of History. There was an implicit logic to this, at least so far as logic has anything to do with progressivism: Having vanquished the specter of racism by electing THE FIRST BLACK PRESIDENT, now America would purge the shadow of sexism by electing THE FIRST WOMAN PRESIDENT, but unfortunately for The Right Side of History, swing-state voters had other ideas. And the defeat of Hillary was a shattering blow to the mental health of millions who had taken seriously the Clinton campaign rhetoric. Such a defeat would have unraveled the minds of Hillary’s core supporters no matter who the victorious Republican candidate had been, but Trump was the pluperfect Hegelian antithesis to the progressive “Right Side of History” thesis, and hence the craziness of 2017.

The psychological history of Trump Derangement Syndrome is important to understanding the story Kat Rosenfield tells about the symbolic value that many people attached to the DNA results they got from 23andMe. For too many people, politics is not merely a contest for control of government policy, but a moralistic expression of personal identity. If you psychologically project upon your chosen candidate this kind of value — representing not merely your policy preferences, but a moral symbol of your personal identity —losing an election leads to an existential crisis. And this crisis is liable to be most extreme for those whose sense of identity is fragile.

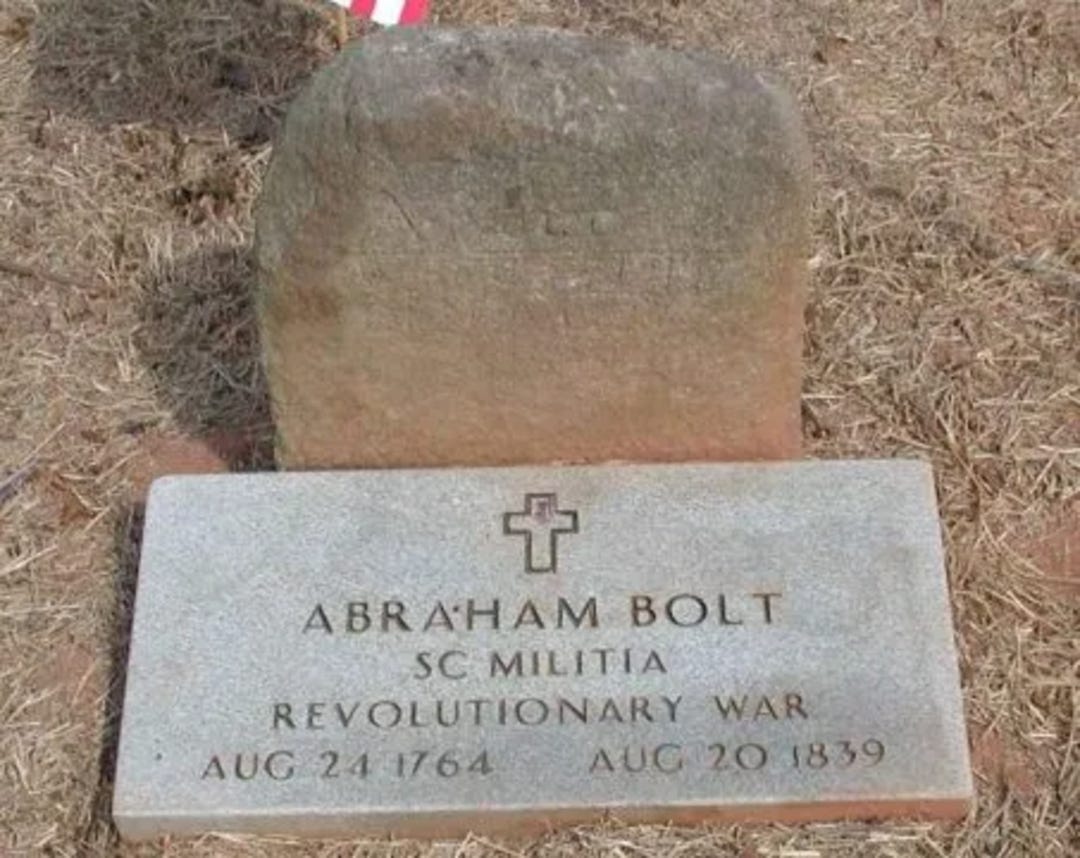

Here’s the thing: I know who I am. No DNA testing is necessary for me to know who my ancestors were. Four generations of them are buried in a couple of church cemeteries in Randolph County, Alabama. And I can go back a pretty long way in my genealogy; on my office wall is a family tree showing my ancestors all the way back to my great-great-great-grandparents (all 32 of them), and you know something? They were 100% American. Every one of my ancestors going back to before the War of Independence was born in America, including the South Carolina teenager, Abraham Isham Bolt, who fought in the pivotal 1781 Battle of Cowpens.

A robust sense of identity is a sort of inoculation against the “Woke Mind Virus,” which explains a lot about the bizarre fascination with DNA testing that took hold after Oprah Winfrey’s 2017 recommendation of 23andMe. Kat Rosenfield examines “the tale of a zeitgeist fueled by both the self-loathing of white liberals and a reflexive anti-Americanism throughout the mainstream.” A major reason many white liberals were so interested in 23andMe was because of the possibility that they might learn they weren’t 100% white. If they could only find a single percentage point of ancestry that was non-European, they could identify as Official Victims of Oppression.

This wacky worldview is inherently anti-American, as Rosenfield explains:

We are a nation of people whose ancestors were drawn explicitly by this promise: that to be American was to unbind yourself from history, from ancestry, because here, you had the freedom to be anyone you wanted.

For the past decade or so, for a certain type of person, that freedom has been positioned as a source of shame. This person thinks that to identify as American is gauche and unworldly; he finds the American flag vaguely embarrassing, perhaps even racist; he seeks comfort in hyphenated modifiers that mark him as other-American, an outsider on the inside. This person will tell you that America has no culture—or that if it does, it’s only a trashy, hollow aggregate of good things we stole from better people than us, and passed through the twin meat grinders of oppression and colonization to yield a dollar-store, fast-food, NASCAR-flavored slop.

And for the past decade or so, this person was more or less in charge of telling other Americans how to feel about America, which is to say: bad.

It is rather ironic that many of the most patriotic Americans today are descendants of either the Irish who fled the Potato Famine of the mid-1800s, or the “Ellis Island” immigrants who arrived here circa 1880-1925. Both these groups were widely viewed with suspicion or hostility by Americans back in the day. Indeed, a sudden influx of Catholics from Ireland and Germany in the 1840s — the Irish fleeing the Famine, the Germans fleeing revolutionary upheavals in their homeland — gave rise to a new political party known to history as “The Known-Nothings.” The boom times of American industry after the Civil War, and the continued woes of Europe, brought about the Ellis Island influx of Italians, Poles, Hungarians, etc., whose increasing numbers gave rise to new concerns about immigration. This concern found its clearest expression in an 1896 article by Francis A. Walker:

The entrance into our political, social, and industrial life of such vast masses of peasantry, degraded below our utmost conceptions, is a matter which no intelligent patriot can look upon without the gravest apprehension and alarm. These people have no history behind them which is of a nature to give encouragement. ... They are beaten men from beaten races; representing the worst failures in the struggle for existence. ...

Within the decade between 1880 and 1890 five and a quarter millions of foreigners entered our ports! No nation in human history ever undertook to deal with such masses of alien population. That man must be a sentimentalist and an optimist beyond all bounds of reason who believes that we can take such a load upon the national stomach without a failure of assimilation, and without great danger to the health and life of the nation. For one, I believe it is time that we should take a rest, and give our social, political, and industrial system some chance to recuperate. The problems which so sternly confront us to-day are serious enough without being complicated and aggravated by the addition of some millions of Hungarians, Bohemians, Poles, south Italians, and Russian Jews.

Perhaps the reader is descended from the “masses of peasantry” of which Walker wrote with such alarm, and certainly it is not my intention to insult the reader’s ancestors. Rather, my point is to convey how the Ellis Island immigrants were viewed at the time, before explaining how it is that the great-grandsons of those immigrants are today so often part of the Make America Great Again (MAGA) movement.

First, in the aftermath of World War I and the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia, there arose a new concern about immigrants, namely that many of them were involved in radical politics. We were importing not just foreign people, but also importing foreign ideas, and the resulting “Red Scare” finally helped coalesce a congressional majority to pass the Immigration Act of 1924, which had the effect of dramatically lowering the pace of new arrivals. This remained the law of the land for more than four decades, which gave the descendants of the Ellis Island immigrants the time necessary to assimilate to American culture. Even if the Poles, Italians, Hungarians, etc., were still in some sense viewed as outside the mainstream, the children and grandchildren of the earlier immigrants were speaking English and participating in society beyond their ethnic enclaves. And something else also happened: World War II, and the Cold War, and the wars in Korea and Vietnam. From 1941 onward, the U.S. military was the crucible in which many millions of young men of differing ancestries were molded into the one-size-fits-all uniformity of American patriotism.

By the 1970s, you could scarcely find any American citizen who was not connected ancestrally to the troops who fought the nation’s 20th-century wars. If you had not served in the military yourself, your father or your brother or your uncle did, And that kind of personal connection to history has a powerful influence on how you view America and its role in the world. My father was wounded within an inch of his life in WWII, my uncle was in Vietnam, my wife’s brother served in Iraq — I’m red-white-and-blue, baby, and I’m sure the same holds for all the Pulaskis and Messinas who can rattle off their own list of family members with military service. We do not find “the American flag vaguely embarrassing,” and cannot understand those who do.

Patriots are invested in America’s continuing success. This does not mean that we are reckless jingos, or that we are incapable of recognizing actual problems in our nation’s past (or present). Is it possible to scan American history and find questionable policy decisions, to put it mildly. For example, the Spanish-American War was inaugurated on spurious pretexts (“Remember the Maine!”) and put the U.S. into the overseas empire business, and as to Korea, don’t ever think you’re going to convince me what a fine guy Harry Truman was, OK? If you want to go through American history looking for faults and failures, no doubt you can find your own pet grievances, but who wants to be a full-time Howard Zinn ax-grinder like that?

We are now in this midst of a national “reset,” like the aftermath of LBJ-era liberalism, and people are trying to make sense of what we’ve been through in recent years. The bankruptcy of 23andMe may indeed signify what Kat Rosenfield sees as a collapse of grievance-oriented identity politics. My own suspicion is that 23andMe lost its mojo once people became aware that their DNA could be used to help identify criminals via forensic genealogy, e.g., “The Golden State Killer” case. The excitement of discovering you’re 2.3% Iroquois or whatever got offset by the cost/benefit analysis of potential downside risks to putting your DNA into a database somewhere. (How many people in Oprah Winfrey’s audience are the cousins of serial killers? We don’t know, but the number is almost certainly larger than zero.)

It’s easy for me to laugh at the collapse of 23andMe because (a) I don’t need a DNA test to know who I am and (b) if you want my DNA, you’ll need a warrant. And perhaps it’s easy for me to jeer at the Identity Politics Grievance Festival because, after all, I’m a heterosexual white male — the Great Oppressor, according to the critical theory crowd. But do we really want to get into a grudge-holding contest? Because it’s not like I’m incapable of grudge-holding. My ancestors almost certainly held a few grudges in their day. Take another look at that 1903 photo of my great-grandfather’s family at the top. As I have explained before (“Why Do We Celebrate July 4”), my great-grandfather Winston Wood Bolt was the great-grandson of Abraham Bolt, who served in the South Carolina militia at Cowpens.

What might my great-grandfather have thought of the U.S. government during those two years he spent as a prisoner of war at Fort Delaware after being captured at Gettysburg? Hell, there probably wouldn’t have been any U.S. government — no United States at all — if not for the Carolinians whupping Tarleton’s ass at Cowpens, and this is how they’re repaid? So, yes, there might have been a grudge or two.

Well, let bygones be bygones. We ought to study history to benefit from its lessons, rather than to go rummaging through the past looking for something to be angry about. Our personal connection to history ought to be a source of patriotic pride, rather than anti-American grievance. You don’t need a DNA test to figure this out.

I think you're right about the clawing for grievance material on the part of many who used those DNA testing services (although I'm sure there was genuine curiosity and some tech whiz-bang aspect for some as well). Yet, let's say they find that they potentially had some non-white ancestor some generations back. So what? What are they making of their own life? And if they do take that smidgen of non-white nucleotide to mean something, what are they saying? That we should go back to one-drop rules? Determine who's an octoroon or a quadroon? Start calling Barak Obama a mulatto? Or Kamala Harris a "cape colored"? It reminds me of a line I heard attributed to Leonid Brezhnev when the politburo was arguing over some Jewish-related issue: "anti-Semitism is making us stupid". It's the same thing here, anti-white racism is making them stupid.